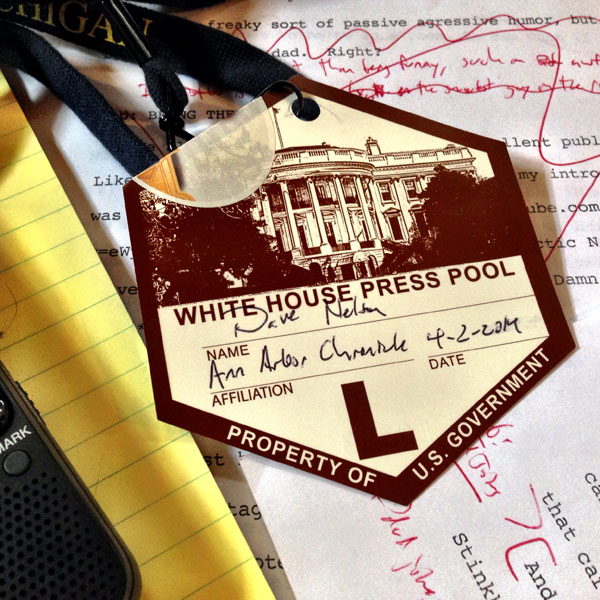

On April 2, 2014 the President of the United States came to the University of Michigan to speak about minimum wage. I covered The Event for the Ann Arbor Chronicle, but didn’t at all speak to the nominal topic of these remarks (i.e., minimum wage), because I don’t feel that events like these are really at all about substantive discussions of policy. They are about handshakebabykissSMIIIIIIIIILEgoBlue!!!–and the PotUS perforned admirable in this regard.

But for those who read the column and really *do* want to think more about minimum wage, here are some articles that have influenced my thinking (with commentary). I also touched base via email with Adam Stevenson (an econ lecturer at U-M mostly known for his work on the labor and tax ramifications of same-sex unions). The sense I got from Stevenson–who describes his position as “pretty orthodox,” basically running along the lines of what you’ll find in any halfway decent Econ 101 textbook–is that increasing minimum wage is in no way the clear win-win the PotUS was pitching to his 1,400 gathered listeners on April 2:

1) Increasing the minimum wage obviously HELPS folks who already have minimum wage jobs (i.e., employers don’t start eliminating job when the minimum wage increases). These workers will have more money, and will spend it on stuff. Economic growth!

2) Increasing the minimum wage HURTS people who are unemployed and basically only qualified for a minimum wage job (i.e., when the wage floor goes up employers avoid staffing vacant minimum wage jobs and creating news ones). These non-workers will continue to have basically no money, and won’t buy stuff. Misery!

2a) The bulk of minimum wage workers are “teenagers and the elderly” [UPDATE: It turns out that this is a pretty contentious statement; details below] Stevenson mentioned this because minimum wage issues can at least in part explain the very high (~25 percent) unemployment among these potential workers, and tends to indicate that raising the minimum will make things even worse for those folks. I’m mentioning it because in his speech the PotUS said that “the average age of folks getting paid the minimum wage is 35.” I believe this is likely true–because the *average* of 17, 17, and 70 *is* 35–but it doesn’t mean that many 35-year-olds necessarily earn the minimum wage. Using a mean average to get folks thinking about a median or mode average is a classic How to Lie with Statistics tactic, and the PotUS deserves to be called out on it.

3) No one can really say what the net effect of #1 and #2 are, despite hundreds of academic papers trying to get at just that. The most famous (cited 1500 times, according to Stevenson, and mentioned in the NPR pieces I included among my resources) is a 1994 paper by Card and Krueger, which found no meaningful job destruction when the minimum wage was raised. “This paper launched a thousand responses, many of them quite critical of the methodology. Most subsequent papers do indeed find a negative employment effect, which reinforces the idea that it’s hard to say what the net effect of the min wage is.” Stevenson goes on to recommend this “readable (if slightly technical) paper by Dave Neumark, one of the country’s major experts in the area. Neumark tends to be critical of the Card and Krueger paper I mention above, but I think he gives all sides a reasonably fair shake.”

4) Increasing the minimum wage is a crummy way to “help the poor.” Noting Stevenson’s point in #2a–that the bulk of minimum wage workers are teens and older workers–relatively few minimum wage workers are “supporting” families in the way we tend to picture when someone says “helping working families.” What *does* “help the poor” and “support working families”? Quoth Stevenson: “The EITC (Earned Income Tax Credit) is a much bigger, better, and direct way to achieve the same goals. Things like subsidized health care, child care, etc. would also be of much larger practical impact.”

In other words, since we have every reason to believe that futzing with the minimum wage is a crummy way to actually help working families and “think of the children” (see #4), then the real question is whether the individual joys and trickle-down-ish benefits of a higher minimum wage (#1) are large enough to cancel the individual misery and deadweight losses (#2)? Stevenson’s conclusion:

The likelihood that the benefits of increasing the minimum wage outweigh deadweight loss “is not clear empirically, and the simple theory (let me stress the many connotations of the word SIMPLE) suggests that there must be a net loss.”

UPDATE Several readers contacted me about Stevenson’s apparent claim that the bulk of minimum wage workers are “teenagers and the elderly”, as well as my implication that roughly 2/3 of the minimum wage working population is teens (i.e., the bit where I said the PotUS may have been accurate in saying that “the average age of folks getting paid the minimum wage is 35” since the average of 17, 17, and 70 is 35.)

To take the easiest one first: I didn’t intend to imply that 2/3 of all minimum wage workers are teens; I was just trying to offer a very simple example of how an average based on extremes can result in a mean that isn’t really representative of the median or mode (i.e., even though the average age of a minimum wage worker is 35, relatively few minimum wage workers are 35-year-olds). This was clumsy presentation on my part, and I should have flagged those numbers as a rhetorical flourish, not an actual characterization of fact.

Folks took more serious issue with Stevenson’s characterization of minimum wage workers as “teenagers and the elderly,” with several readers pointing to this report from the US Dept of Labor: Characteristics of Minimum Wage Workers: 2012, and specifically to Table 7. An anonymous reader from the Chicagoland Area wrote:

Matt Wilson made much the same point over Twitter, pointing out that “teenagers are 25%, 65+ are 2.5%.” (these numbers differ because Matt is looking at all workers at or below minimum wage, while the Chicagoland Reader is looking at just those specifically earning minimum wage). Matt goes on to point out that the mode–i.e., the most frequent age of a minimum wage worker, as presented by the US DoL–is 20–25yos (that segment constitutes 26.5 percent of the total minimum wage workforce).

In Stevenson’s defense, I believe that my presentation may have overemphasized this point, which really was a passing aside in his email. The full sentence was “The people who hold and want these types of jobs tend to be teenagers and the elderly.” Upon reflection, Stevenson’s “tend to be” is a much softer wording than mine (I characterized these groups as the “bulk” of minimum wage workers, which they clearly are not). Looking at the US Dept of Labor table, Stevenson’s characterization of a “tendency” strikes me as at least fair, in that taken together these groups (workers below 20yo or above 65yo) comprise just over 26 percent of the minimum wage workforce.

Meanwhile, only 8.6 percent of the workforce paid at or below the minimum wage is 30–34-years-old, and 5.7 percent is 35–39–which brings me back to the core point of #2a: Although it may well be true that the *average* age of a minimum wage worker is 35, that doesn’t mean that very many 35-year-olds are stuck trying to support a family on $7.25/hour.

Sincere gratitude both to Matt and the Chicagoland Reader for calling me out; on the one hand, I really wish I’d thought to dig into these numbers earlier, because they’re really interesting. On the other, I’m sorta glad I didn’t, as these are the sorts of numbers I could get lost in for hours. Thanks!