Penn & Teller Explain Ball & Cups on Jonathan Ross 2010.07.09 (Part 2) – YouTube

This presentation of the cups and balls (a trick that is downright “*ancient*) isn’t just an incredibly graceful and concise primer on magic, but also on that triple-point of storytelling, narrative, and persuasion. It highlights the shared, emergent linchpin that’s vital to entertaining someone, explaining something to them, and getting them to see things the way you want them seen.

How wanna be a good writer? And I don’t mean “a good novelist” or “a good copywriter” or “a good essayist”–I mean good at all three, good at the stuff that’s way down below all of these visible structures, down in the roots? Then you could do much, much worse than watching this video over and over and over again.

Category: Other Writing

See Project Orion! To Mars in an A-Bomb-Powered Sleigh!

For those who’ve never heard of Project Orion, Wikipedia is as good a place to start as any:

–which, yea, sounds pretty patently nuts. But keep reading, and it begins to look *really* attractive:

They actually made demo prototypes of this bomb-drive, in order to convince government backers that it was *less* nuts than it sounded, and it does indeed looks pretty rad:

Project Orion: “To Mars by A-Bomb” RARE Footage – YouTube

Here’s the full declassified footage those clips are culled from:

Project Orion [nuclear propulsion] (1958) – YouTube

Anyway, if this lil sidebar in the history of the atomic bomb tickled your fancy, then you can do worse then losing a few hours sifting through Alex Wellerstein’s Restricted Data blog. Start here: The “Secret” song | Restricted Data

How the Textbooks Get Made (or “The Writer’s Life for Me”)

I continue to write a monthly column for the Ann Arbor Chronicle. In the latest I take a break from talking about guns and “gun control,” and instead talking about my actual work-life as a freelance writer/editor:

The Ann Arbor Chronicle | In it for the Money: Not Safe for Work

I hunt down these articles, then revise and massage them so that they’re high-school accessible, because that’s the market for this book – high school libraries. That’s my job:

I write reference works on pornography aimed at high schoolers.

I’ve also done books like this on drugs and teen sex. I don’t even know what to say about my life, except that if you had told 12-year-old me that this was how it was going to end up, that kid would high-five you all over the place.

The only time a lay person hears about what goes into a textbook is when some jerkwater school board in North Carolina mandates that they aren’t buying anything with this untested evolution crap in it, or whatever.

I’ve done this about a dozen times (not counting projects I ultimately passed on because the money or timing were wrong). And I gotta tell you, the editorial guidelines have never remotely approached that kind of political micromanagement. More than politics, “expedience” and “balance” are the rule.

. . .

The Coworking Society: My Day Not-Job

First off, sorry for the week of radio silence; I was traveling for Spring Break with my wife and kids. I’d assumed I’d have a chance or two to update the Snip, Burn, Solder Blog while on the road, but instead ended up investing my writing pomodori in a new short story (not to spill the beans on it, but there’s Chicago’s elevated train, pickpockets, and naked folk in the story. I think we can all agree these will have been words well spent). All apologies, no excuses.

Secondly, this interview (conducted by the remarkably patient Mark Maynard) is now up: Inside Ann Arbor’s Workantile coworking community. It’s an +8,000 word (!!!) interview with me and the other two “owners” of the “Coworking Society,” and absolutely and profoundly unprofitable LLC whose sole purpose is to support the Workantile, a community of freelance and independent workers who share goodwill and a *lovely* 3000-square-foot workspace in downtown Ann Arbor, MI.

Here’s an interview snippet:

BILL: Again I want to unpack the assumptions here a bit. If you mean: are there work collaborations between members? Not much. We all pretty much have too much work already. There are ideas for new things, and at least a few of them have gone somewhere. But we all understand that whenever we launch a new Next Google, our dance cards are immediately filled with appointments with investors or for a boot stamping on our faces–forever. So that outcome tends to be a self-trimming branch as far as Workantile is concerned.

. . .

DAVE: Just to take a sec and disagree with my distinguished colleague: I’ve seen and participated in a fair amount of “billable work collaboration/hook-up” in the Workantile–but I don’t think this is unusual in any community. I know folks who are deep into their communities of faith; those are their goto communities, and if they’re looking for a lawyer or writer or graphic designer or builder, those are the people they ask. This is the same at Workantile, except for without the God business. When I needed a tech reviewer for the electronic projects in my very enjoyable book of geeky crafting, I ended up hooking up a Workantile member (the one that designed and built our original computer-controlled door system, in fact). When another member needed someone to write content for web sites he develops or do some of the coding for those sites, he asked around Workantile. The writing group I’m in now–and, with whose support, I’ve done my best work–was introduced to me by a Workantile member. Our email group regularly has threads that start with: “Hey; I need a contract looked at; what lawyers do you guys trust? My sewer pipe is collapsing; what plumbers do you trust? I wanna buy ethically raised pork; who knows a pig guy?” I think maybe what Bill wants to foreground is that this sort of commerce isn’t our *purpose*, just a by-product–but what *I* want to foreground is that commerce is the human business, and whenever humans are in a group fungible exchanges are brewing. Dogs sniff butts, we recommend organic CSAs, but it’s all the same.

So, if you’ve been wondering what “coworking” and “coworking spaces” are all about, or the ways folks do “Work 2.0” (or whatever damned thing WIRED is trying to call it now), then there are worse places to start than this interview.

Running the Gun Numbers: The Quick, the Dead, and Intent

My latest column for the Ann Arbor Chronicle is up; consider it part two in the series “Things We Need to Talk About Before We Can Talk About Gun Control” (part one is over here):

The Ann Arbor Chronicle | In it for the Money: Running Gun Numbers

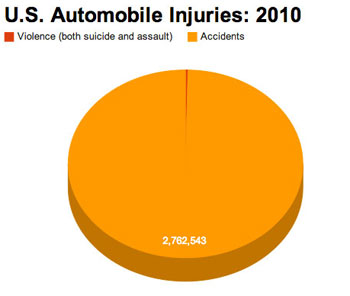

But, the thing is, of those 2,771,497 automotive injuries, only 8,954 were acts of malice or sorrow, and only 1,789 were attempts at suicide [10].

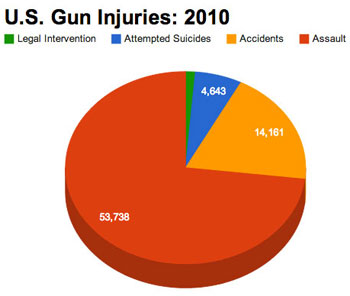

Check the pie charts: Orange represents blameless accidents; red and blue (and green) represent active human efforts to inflict pain or suffering. We’d have included a pie chart of Automobile Deaths, but it would have just been an orange circle.

In other words, those 2.8 million car accidents were basically just that: accidents. Those 33,000 corpses on the highway were largely the result of bad decision-making and bad weather, bad maintenance and bad luck. Meanwhile, our 30,000 gun deaths weren’t accidents – sorry, 4% were accidents. The rest were acts. They were deliberate expressions of hate and sorrow and frustration and desperation. That should mean something to us as human beings.

RECOMMENDED GAME: “Pipe Trouble”

Spoiler Alert: I don’t believe in Good Guys and Bad Guys, and don’t really believe in the narrative necessity of antagonists and protagonists or the centrality of Conflict. Stories, to me, are about Problems, and the most interesting Problems are the ones that arise when everyone thinks they are basically the Good Guy Doing the Right Thing. Subsequently, most video games bore or frustrate me. That said, I’m loving Pipe Trouble, the newest new-media thingy from affable pop-culture gadfly Jim Munroe.

I dig games that 1) interestingly model real-world conundrums (however abstractly) and 2) force the player to balance competing interests in a Universe where there is never (or rarely) a zero-loss win-win. Add in adorable high-rez 8-bit graphics, interestingly quasi-narrative faux CBC radio clips between scenes, and reasonably ramping difficulty (I’m crappy at most traditional video games, so you kinda gotta take it easy on me), and this is just a perfect-fit game for dave-o.

Added bonus: Playing this game with my 6-year-old catalyzed a great conversation about 1) how to balance the stress of being challenged with the enjoyment of playing (levels get steadily harder and faster, which mega wigs both me and my kid out), 2) balancing economic development and environmental conservation in energy policy, and 3) how competing interests aren’t generally ones of “good guys” vs. “bad guys,” but situations where various groups are disagreeing because they have different visions of what constitutes the Best of All Possible Worlds, and their actions–no matter how destructive–come out of a good-faith effort to Do the Right Thing.

You can play a trial version online for free before buying–but I’m telling you, this is worth the price of a decent cup of coffee. Go get it for iPad or Android thingy.

MI voters: Plz take 10 seconds to help preserve public education in Michigan! Plz Share & RT! #PureMichigan

UPDATE MARCH 20, 2013: Although this stupid bill made it out of committee unamended (boo!), it still needs approval from the House–so call or email your rep ASAP and repeatedly! The sample letter below still applies. Thanks!

If you live in Michigan and give a crap about local-control of the public schools you pay for, please contact your rep *right this second*–you can even crib from my letter, included below!

The state House Education Committee will likely vote this afternoon on House Bill 4369, which expands the Education Achievement Authority “takeover” district (currently dicking things up big time in Muskegon Heights and throughout Detroit) to a statewide entity . I wrote about this extensively back in December–the bill numbers are different, but the bad plan remains the same. The website of the Michigan Educator’s Association (I.e., my wife’s union) has a concise bit on the current bill.

Here’s the letter I just sent. You can use it if you want, modify it how you choose, customize it to best speak to your concerns and community–just write your rep and do it *RIGHT NOW!*:

Dear __________________,

Please do everything you can to oppose any expansion of Michigan’s as-of-yet unproven Education Achievement Authority, and to limit the implicit privatization of public education in Michigan. This includes opposing House Bill 4369 (which expand the Education Achievement Authority to a statewide entity composed of charter schools). I have deeply held philosophical reasons for opposing the operation of our public schools on a for-profit basis.

Handing over our public institutions – and tax dollars – to private companies with no demonstrable record of success, and doing so without strict oversight, flies in the face of reason and should offend rational, honest public servants on both sides of the aisle.

For a detailed analysis of the hazards of pitfalls inherent in the EAA, charter schools, and “cyber” schools, please take a few minutes to read this 2012 article by Ann Arbor Chronicle columnist David Erik Nelson: http://annarborchronicle.com/?p=102112

Thank you for your time, consideration, and good faith.

Sincerely,

NAME

ADDRESS

(Obviously, plugging my old column is totally optional–but the details are all there, and the concerns for citizens laid out clearly, with citations and everything!)

The MEA suggests contacting both your own rep and the entire House Education Committee. I agree with this strategy; info for the entire Committee is pasted below:

(And here’s all those emails in one easy-to-copy&paste-string: LisaLyons@house.mi.gov, RayFranz@house.mi.gov, HughCrawford@house.mi.gov, KevinDaley@house.mi.gov, BobGenetski@house.mi.gov, PeteLund@house.mi.gov, TomMcMillin@house.mi.gov, ThomasHooker@house.mi.gov, BradJacobsen@house.mi.gov, AmandaPrice@house.mi.gov, KenYonker@house.mi.gov, EllenLipton@house.mi.gov, DavidKnezek@house.mi.gov, WinnieBrinks@house.mi.gov, ThomasStallworth@house.mi.gov, ColleneLamonte@house.mi.gov, TheresaAbed@house.mi.gov)

Thanks! GO FORTH AND HASSLE YOUR ELECTED REPRESENTATIVES! Be the Boss!

RECOMMENDED READING: The Last Policeman by Ben H. Winters

The Last Policeman is a really enjoyable read, both as a literary novel and as a low-grade mystery/crime thriller. About 60% into the book you suddenly realize that the crime has been solved and all loose ends secured–which leaves one to wonder what the hell is going to occupy the remaining pages. At this point, though, the investigator tracks backward through his solved mystery (not temporally, just in terms if the relationships of cause and effect), and unwinds a whole second layer to it all. So, right there, it would be a great piece of mystery writing, wonderfully managing expectations and non-cheating reveals (a la the best of Christie or Doyle). Throughout, it’s also great crime writing, showing the way that ordinary folks can resolve–without cognitive dissonance–the mismatches between their external and internal lives (I think of Price’s Clockers as being the epitome at this aspect of crime fiction). This is all pinned against an almost classic SF backdrop: Impending meteor strike is gonna end the world on a known date. Everything that means for workaday humans–including this fair-and-square regular-joe cop who’s found himself suddenly bumped up to detective–brings these “lowly” genre pieces up a notch. It’s fine *craft* being used to explore the poignant humanity of Kobayashi Maru, which is basically the thing we mean when we say “art,” right?

Takeway: Read this. It’s a quick one and worth your time.

(DISCLOSURE Those are indeed Amazon affiliate links to the book; if you click on them and buy it, I’ll get some minuscule percentage. Also, the book itself was a gift from my mom; all of these factors may have swayed my opinion. I’m only human.)

On Guns and Control, Tools and Instruments, the Quick and Dead

I’m back to writing a monthly column for the Ann Arbor Chronicle. February’s column kicks off a series on guns (and largely builds off thoughts I posted here back in January). If you have experiences of guns–your actual first-hand experiences–that you’d like to share, please feel free to hit me over Twitter or email.

The Ann Arbor Chronicle | In It For The Money: Guns And Control

But most of all, it requires attention – all of your attention. You are exquisitely focused when you are holding a gun – and not just because the gun can hurt or kill anyone nearby, including you. (Our cars are far more likely to hurt and kill anyone nearby, and we zone out behind the wheel all the time.)

There is an essential quality to this instrument compared with others; its nature is to make us aware of how vital and powerful our attention is, in and of itself. I don’t look at my father when I’m holding my loaded shotgun. I don’t look at my son when I’m holding my loaded pistol. I look at the target – only at the target, because whatever I’m looking at is the target.

“Light Motif” and Taking Hi-Res Pinhole Digital Snapshots

Last month I wrote a piece for The Magazine about glass-lens vs. pinhole photography, and a little $40 accessory my brother-in-law manufactures and sells that allows you to take old-school, genuine pinhole snapshots using high-end Micro 4/3 digital cameras. The article is currently available for free reading over on The Magazine‘s website:

Light Motif — The Magazine

You and I both know that no architect designed a roofline with that curve, and no masons tried to build it that way. This image is grossly distorted, but every image coming through a lens has at least subtle distortions corrected by optics and electronics.

A pinhole camera creates no such distortion because it never alters the path of any photon. Instead, it sharpens an image by massively reducing the number of photons that reach the image plane. Blurriness, in part, is caused by a “point-to-patch” correlation between object and image, where photons striking a given point on the object scatter at slightly different angles and thus strike over an area of the image plane, rather than at one point. By blocking these stray photons, the pinhole brings us closer to an ideal point-to-point correlation between object and image.

FYI for Writers: The Magazine has been a great publication to work with, as a freelancer: Good pay, good editors, an excellently fair contract, and really solid exposure and promotion of your work. If you’ve got an article in your that suits them, you owe it to yourself to pitch it.