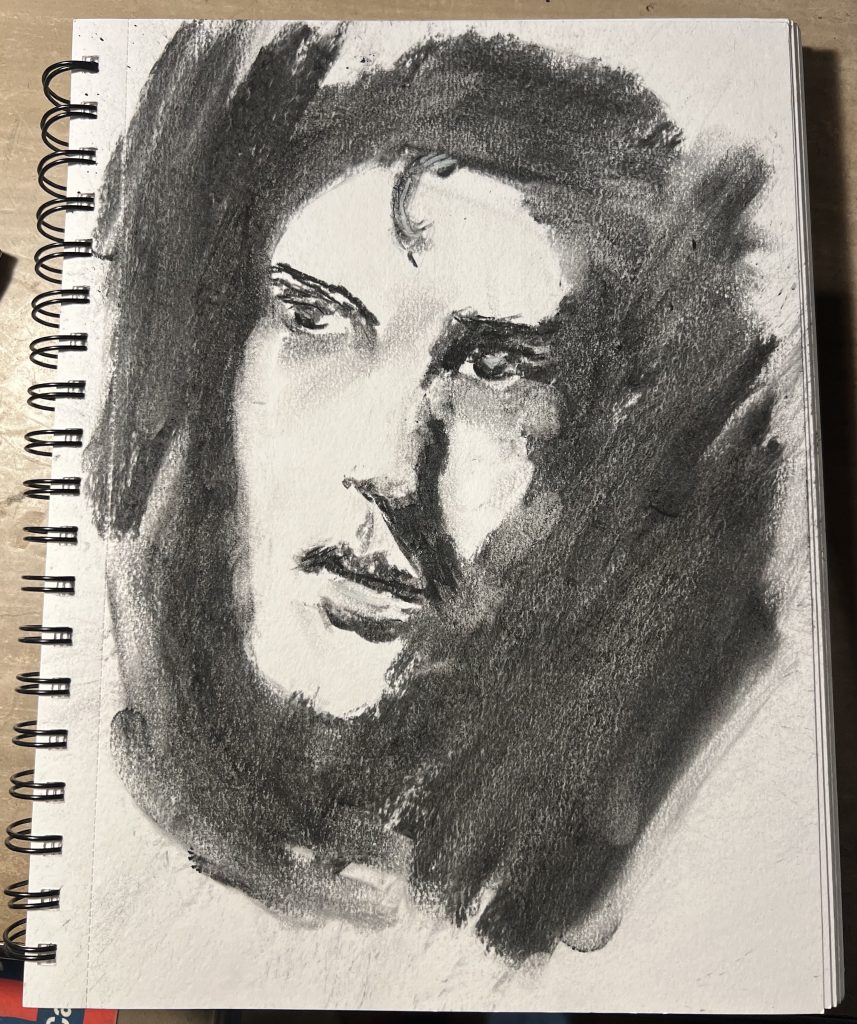

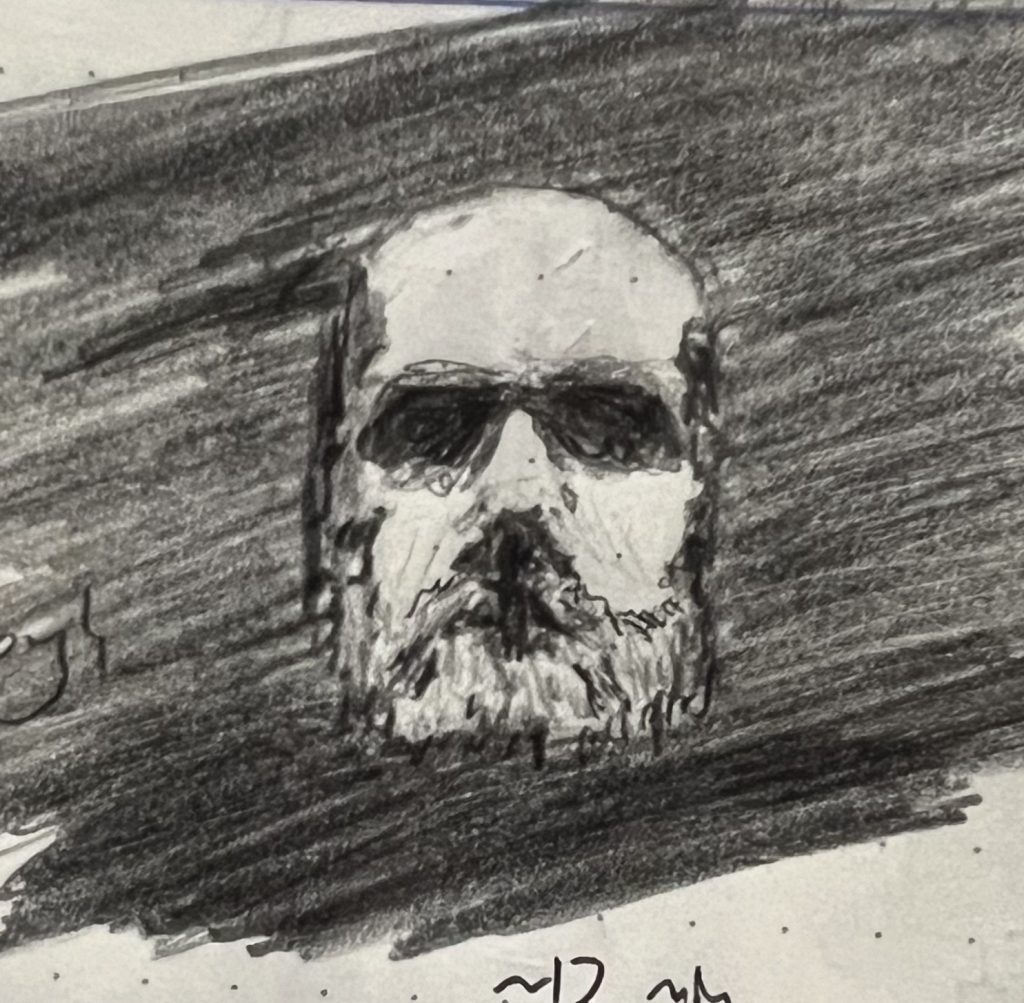

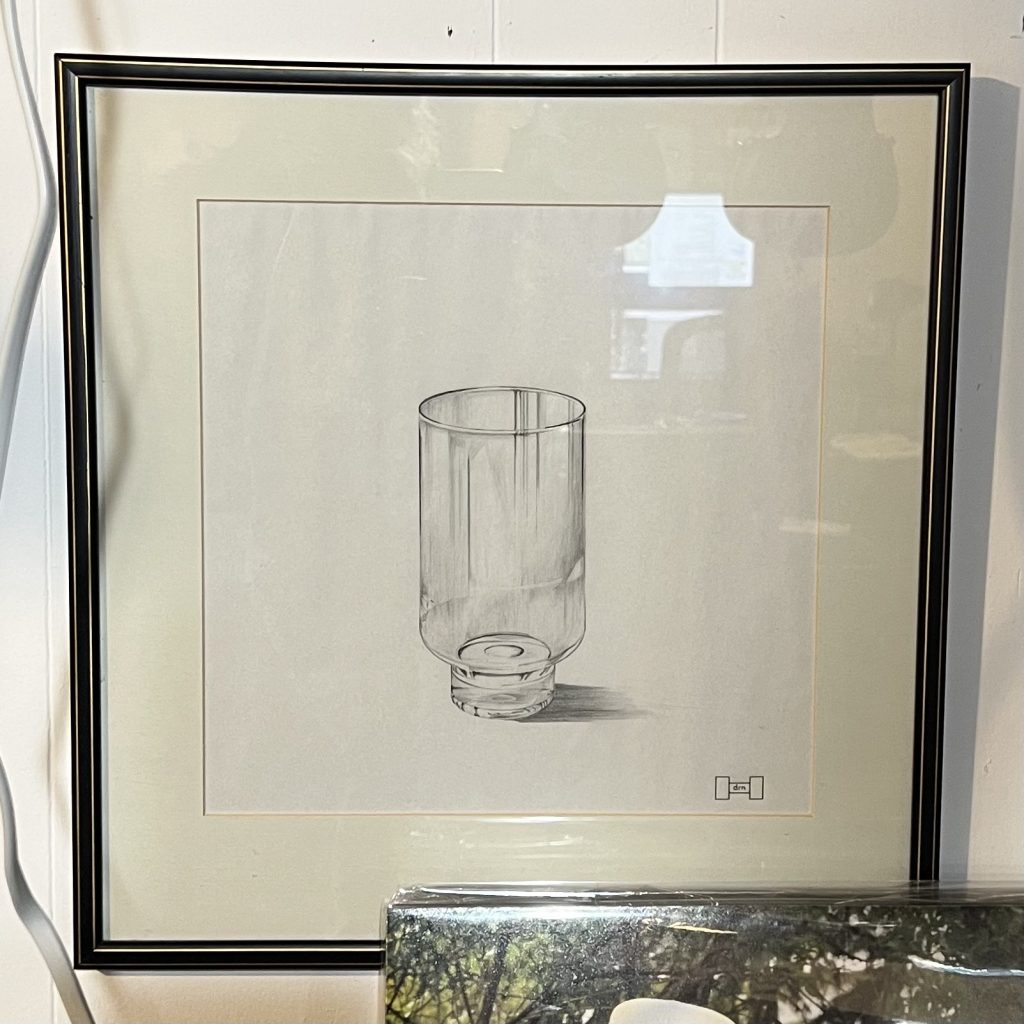

This is my second attempt at sketching in charcoal. Instead of using a charcoal pencil (as I did in my first stab, which I wasn’t happy with), I used some old willow charcoal my wife had kicking around. This stuff is literally just charred sticks. It’s not nearly as dark as charcoal pencils, tending to more gray than black. But it is so soft that you can practically erase a line just by rubbing it out with your fingertips. It’s a blunt tool, but incredibly forgiving. As you build up layers of it working toward black, it basically grinds down to powdery ash. Drawing with it is half drawing and half finger-painting. Very fun and liberating, if you can release yourself from needing to control how things go.