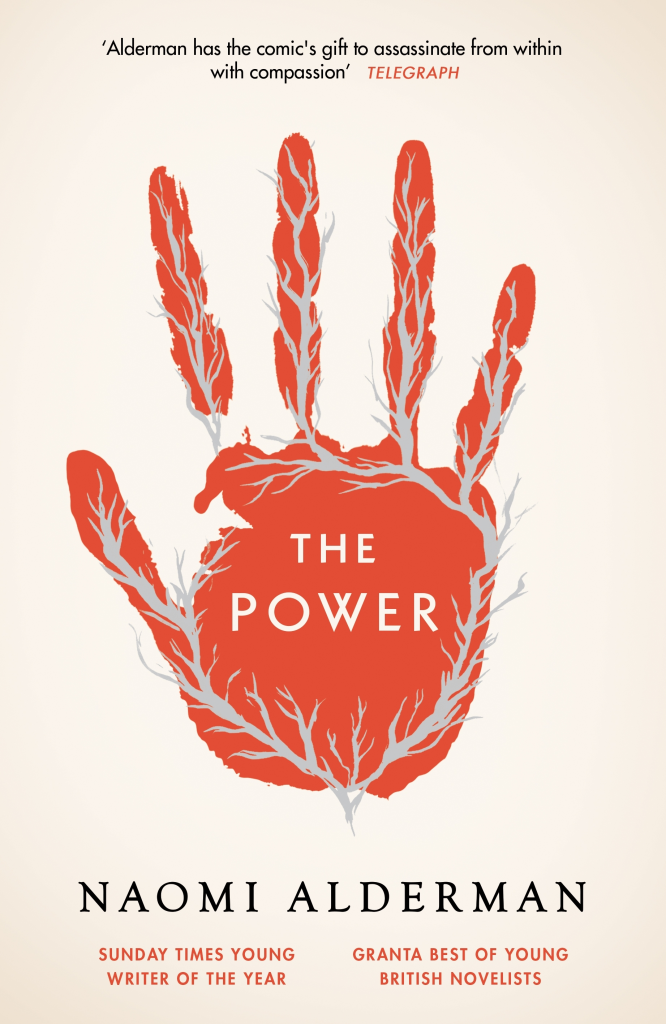

Before this year, I had no clue The Power or Naomi Alderman existed—despite the acclaim the book met when it was published in 2016, and the fact that its apparently been made into an Amazon mini-series starring Toni Collette, who I absolutely love. A colleague in a crit group read a story I was working on, and recommended I read this. She was absolutely right.

When I say this is the bravest and most horrifying book I’ve read in ages, I’m not exaggerating. I actually had to stop about 10 minutes from the end because I was in a Thai restaurant in Orlando and was on the verge of bursting into tears, and didn’t want everyone staring at me. This book is easily better, and darker, than Atwood’s Handmaid’s Tale (both a book and artist I hold in hella high regard).

One clarification: when I told my wife that this book was the bravest and most horrifying thing I’d read in years, she totally misunderstood what I found horrifying in the book. She assumed I was upset by the rapes. There are several very graphic and traumatic rapes of men by women in this novel, as well as broader sexual subjugation of men.

Frankly, none of that really bothered me. I’ve read fictional depictions and non-fictional accounts of the rapes of men and boys that I’ve found more upsetting. Talk to anyone who’s worked for child protective services and you’ll hear an earful. Humans are, on balance, awfully creative when it comes to being awful.

What got me about this book is that, evidently and despite it all, there was some small part of me that had continued to really and deeply believe that “everything would be better if women were in charge.” Alderman meticulously dismembered and violated that foolish, optimistic child that was still hiding inside me.