(This story is brought to you by the generosity of my Patreon patrons. Supporters get access to exclusive horror and SF stories, an odd short film, and more.)

Author’s Note

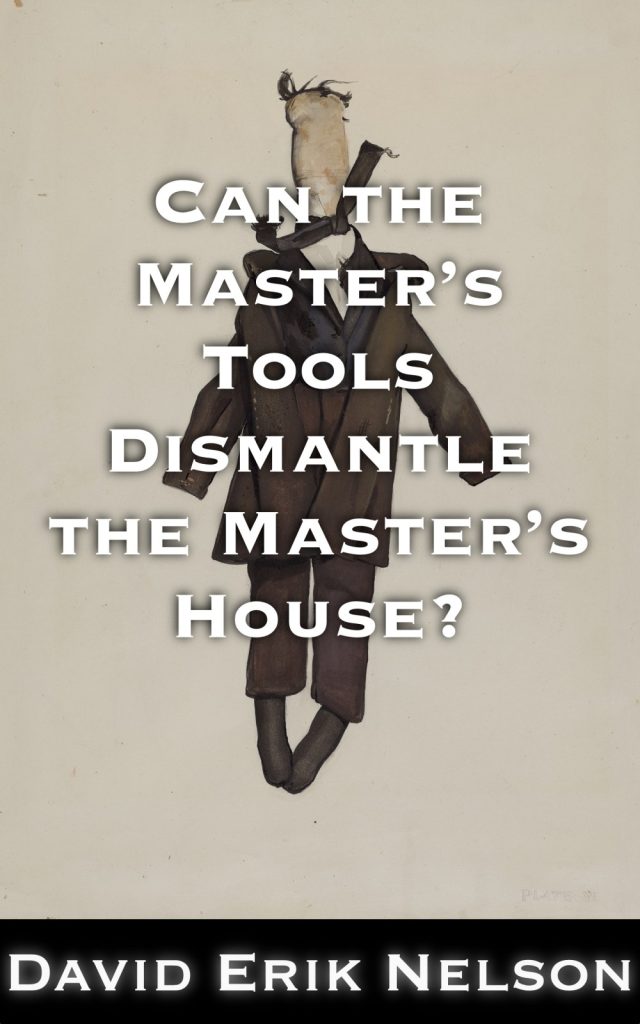

“Can the Master’s Tools Dismantle the Master’s House?” asks the truly pressing question of our time: Should I bring home that rag doll my wife and I found while checking out the fall foliage?

I wrote this story almost four years ago. It’s my COVID story and, in a way, my George Floyd/BLM story—albeit one more about privilege than race.

When I started submitting it for publication (about 6 months into the pandemic) it was turned down as being “too soon/too topical.” Several editors (each of whom have bought longer stories from me since) said basically the same thing: this is too of-the-moment; it won’t age well, or necessarily even really make sense in a few months.

But the thing is, all the stuff I feel like I was talking about in this story, it hasn’t gotten better. If anything, it’s gotten worse. Time hasn’t healed these wounds much at all.

Meanwhile, the story has gotten no closer to publication. Usually, I’d just assume a story that doesn’t sell after four years and dozens of submissions simply isn’t a good story. I’ve written not-good stories. They seem like a good idea at the time, but you look at them again after the twelfth “Thanks, but this isn’t a good fit for us” and realize that the idea might have been good, but your execution isn’t.

But here’s the thing: I honestly don’t believe this is a bad story. I think it’s a good story. But I also think it’s a really uncomfortable story, in a way that’s gotten even more uncomfortable in the last four years. (I also have past experience with that: writing stories that are extremely uncomfortable for most readers, and not understanding that until the story has been rejected a few times and some kind soul finally explains what’s glaringly obvious to everyone but me That’s what happened with one of my earliest sales, “Exit Exam, Section III: Survival Skills, Question #7.”)

That said, “Can the Master’s Tools…” might just be a bad story.

Either way, it’s short. I’d be interested in hearing what you have to say about it. I’m on Mastodon at @dave0@a2mi.social, or can be emailed directly: dave@dave0.com

Thanks!

“Can the Master’s Tools Dismantle the Master’s House?”

by David Erik Nelson

It’s your wife, LaSonia, who finds the doll. She pulls it free of the frozen leaves, laughing. You laugh too, laugh along. But looking at the thing makes you want to puke.

There’s really no other way to say it: The doll looks super-duper racist.

Boneless arms dangle and jounce as LaSonia peels away frozen leaves, revealing eyes that are wide white iris-less circles sewn onto a black cotton face. Thick red embroidery-floss lips bend into something more rictus than grin. Mud-matted wooly hairpuffs peek out around a red scrap of kerchief.

Pale, awful somethings—like water-logged corpse fingers or fat white worms—just barely peek out from under the skirts of the black-faced doll’s dark-blue gingham check dress.

You’re so revolted by the squirming white worms that you almost slap the doll from her hands. But you can’t stomach the idea of touching it.

LaSonia squeals, “Oh. My. GOD! I haven’t seen one of these since I was tiny!”

She flips the doll over and pulls the dark check skirt down to reveal another doll—or, really, another half doll. This doll she’s found in the frozen leaves is something you’ve never seen before, a ragdoll composed of two doll torsos sewn together at the waist, “joined at the skirt.” The worms hadn’t been worms at all, but the second doll’s pale arms.

LaSonia later explains that it’s called a “topsy-turvy” or “flip doll.” This one was hand-made, not mass-produced—more collectible, if no less racist.

The second doll’s dress—previously hidden under the Black doll’s dark checked skirts—is a fancy pink block-printed calico. Her pale head has bee-stung lips stitched in the same red embroidery floss as her dark sister’s. Her blue eyes are heavy-lidded. A tangle of yellow yarn hair hangs out below her “Ms Muffet” cap.

“Mommy and Mammy,” LaSonia explains. Two sets of arms, no legs to run away on. “My auntie had one just like this!” she marvels. “She kept hers on a high shelf, alongside her collection of glass whale oil lamps. She got it from Gram”—a.k.a. City Councilwoman Montgomery—“who’d got it from Great-Great-Gram”—the first Montgomery born free—“who swore she’d got it from her own Gram—”

“—who strangled a Johnny Reb, stole his horse, and didn’t stop until she hit Pennsylvania and discovered the saddlebags held an infantry company’s payroll,” you finish numbly.

It’s easy to be proud of LaSonia’s family tree, which is stout and tall and broad and deep-rooted. She’s a bona fide Daughter of the American Revolution. Thirteen generations of Montgomeries have cobbled together scraps of the American Dream. Your own family tree is little more than a hacked shrub with just a single pair of forks: On Mom’s side a couple of scrawny Jewish Kindertransport babies, imported to the UK from Nazi-occupied Poland, malnourished and pale as boiled potatoes. On Dad’s a set of Romanian pogrom orphans. All the rest of that tree? Ash and smoke coughed out of Holocaust crematory smokestacks.

You frown at LaSonia’s doll and mount a weak argument, mumbling “black mold” and “mildew” and “allergies.” LaSonia gives you The Look™. The doll comes home with you.

#

The doll takes up residence on the shelf above LaSonia’s desk—sometimes Mommy-up, other times Mammy-up. “Momma Mammy” watches over every minute of LaSonia’s Zoom lectures and remote office-hours.

You object. LaSonia laughs it off.

“She’s my guardian angel, Abe. Or maybe my Kali,” LaSonia winks, “Destroyer of Negative Forces and Remover of Obstacles.”

In the weeks since she found the doll, LaSonia’s bank inexplicably reversed a fee, a local “Men’s Rights Activist” abruptly stopped hassling her, and her stalled dissertation finally escaped editorial-review purgatory.

“Besides,” she adds, “it’ll be a great addition to the Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia, once the university reopens.”

But you can’t get used to the doll. Seeing it up on her shelf makes you nervous. You’re unnerved by the smugness of the White sexpot in her little cap, childishly revolted by the Black mammy imprisoned under her skirts, ashamed of both these ridiculous feelings.

One night you dream that you hear a scuttling in the front hall. Upon investigation, you discover the doll creeping along the baseboards, tumbling in sloppy boneless cartwheels. She turns to look at you, Mammy-side up. Dark eyes slowly scan you head to toe, unimpressed. Her wriggling black arms lift her skirts, so that the White mommy can peer out. White Mommy winks and pantomimes a smoochie-mouth kiss at you. Then they mount the wall, scuttling like a spider, and squeeze through the few inches LaSonia left open at the top of the window to let in the night breeze.

You awake standing in the hall, alone, your skin stippled with goosebumps.

#

You keep hassling LaSonia about the doll. You can be that way, picking, picking, picking, argumentum ad attrition. Back when you were both undergrads, LaSonia had quit talking to you for a week after you two had gotten into just such a slow simmering argument. It was about that Audre Lorde essay, “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House.” In all honesty, you weren’t even really arguing about the essay, because you’d never read it. You were arguing about the title; the claim felt so transparently absurd: a hammer will smash the patriarchy just as handily as it’ll smash a nail or window or a baby’s skull, right?

But this argument you actually care about. You argue that doll is a pathogen vector. You argue that it probably harbors bird mites. You argue that she should email the curator of the Jim Crow Museum; if he wants it, you’re happy to drop it off on your way to work. If he doesn’t, the thing should get trashed.

LaSonia finally snaps: “If the doll’s so dirty, why the Hell you always playin’ with it, Abe?”

“You’re nuts!” you snap back. You’d never touched the awful thing, not in the woods, and not since she’d brought it into the house. You’d assumed it was LaSonia who flipped and posed the doll at her whim.

The realization comes with an icy and nauseating abruptness: your dream of the doll in the front hallway was no dream. That was something real, which you really saw.

You open your mouth to speak, but your phone saves you from whatever you were going to say. It’s your dad.

#

At the start of the pandemic you and your dad had gotten into the habit of nightly video chats. You’d had never really been that close. But he’ was’s bored, confined home alone, far from the boardrooms and conferences he adores. Meanwhile, as an “essential worker” in a prison infirmary, you’re permitted to leave the house daily, do “real” things, talk to “actual” people. In Dad’s estimation, your life choices have abruptly flipped from mildly disappointing to endlessly fascinating. You’d be lying if you said it hadn’t been a gratifying turn.

“How’s Dr. Puddin’ Pops?” Dad asks.

Does that sound racist? You think it does, but you know it isn’t. The inmate he’s asking about—a once-popular Black actor and comedian, now a half-blind octogenarian—actually was the spokesperson for Jell-O Pudding Pops once upon a time. Back then, he was widely regarded as “America’s Dad.” Now he’s America’s Serial Date Rapist.

Most of the prison population has tested positive for the virus. They have to isolate in their cells. Because America’s Bad Dad is elderly, and thus at high-risk for complications if infected, admin transferred him to isolation in the infirmary with you. The arrangement is half reverse-quarantine, half internship. He sleeps on a cot in your office, makes you both coffee and Cup O’Noodles, answers the phones, and jokes around with your patients via intercom. It probably helps that he played a doctor on TV for so long.

You want to talk to your dad about the dream that wasn’t a dream, about LaSonia and the doll. But you can’t find a way to bring the conversation around After an hour you both say, “I love you” and hang up. You go to bed.

#

The doll troubles you. You can’t talk to your dad about it. So you do the next best thing, and talk to America’s Dad about it.

You two sit together in your little office wearing surgical masks. He’s old, mostly blind, a felon that never finished college, yet still does a better job of looking like a doctor than you do.

America’s Dad listens patiently, hands laced on the head of his cane, his good ear cocked to you.

“Your Black wife found a pickaninny doll,” he reiterates, “and it makes you ‘uncomfortable’?” He chuckles, leaning back, eyes blank but crinkling with that mischievous grin you’d loved seeing on reruns as a kid. “My dad’s doll made me uncomfortable, too,” he reminisces. “Until it was mine.”

Your throat squeaks: “What?”

He gives you The Look™, despite being blind. “You’ve gotta open your eyes, son.”

Maybe he’d have said more, but one of the patients out in the ward buzzes the intercom. “Dr. Jell-O Dad,” the patient calls out to the blind comedian, “Do a Russell!”

Dr. Dad’s milky eyes sparkle. He presses the intercom button and launches into a 60-year-old stand-up bit about his younger brother. That same brother—now a congressman—disowned his big brother on national TV three years ago, sponsoring a bill named after one of Dr. Jell-O’s victims. Inmate NN7687 doesn’t seem to harbor any hard feelings about this.

#

The pandemic has taken away so many things—bars, birthday parties, road trips, libraries, religious services—but it gave us one thing we never would have had otherwise: Visibility. In the months since the stay-at-home orders, we’ve seen the kitchens and living rooms and studies and dens of countless celebrities.

And once you start to see it, you can’t believe you never saw it before:

That schmarmy, bow-tie loving right-wing news guy? There’s a fat, crocheted Mammy on top of his fridge, leaning against a teddy bear cookie jar.

The electric car impresario who seemed to have lost his mind, touting bleach-drinking “miracle mineral water” cures? A clutch of plastic pickaninnies, eyes and lips perfect shocked circles, crowd his side-table.

That erratic former rapper who’s declared he’s running for President on the “Record Release Party” platform—and inexplicably keeps rising in the polls? A faded wooden “Shuffling Sambo” doll sits in his home office’s broad window. Seeing that stung, because your dad and his dad actually sorta-kinda know each other, having grown-up together in the Squirrel Hill neighborhood of Pittsburgh.

Even in the Oval Office you spy a minstrel doll—a “golliwog” in blue jacket and red bow-tie, big eyes and wide red lips surmounted by an explosive shock of picked-out afro. It sits tucked among the framed photos just behind the Resolute desk.

That night on your call with Dad, you must be staring, because he finally cranes around to look up at his own bookshelf. A sock monkey perches there, an old one, made from real Rockford Red-Heel socks: “Mr. Lips.” He’s sat up there for as long as you can remember, leering and repulsive: Thick red grinning lips. Staring white eyes. A big, chipped, wooden button shaped like a fat slice of watermelon sewn to one hand.

Dad turns back. “You know I already promised Mr. Lips to your sister,” he says. “She obviously needs him more; her company is just about to go public on the New York Stock Exchange.”

#

The next day, in the prison infirmary, you ask America’s Former Dad how people get these dolls. He smiles slyly. “You don’t get them; they get you.”

You ask if everyone who has a doll is a total piece of shit like him.

He does not flinch. “No,” he says. He names two prominent judges, a retired basketball player, a CEO, and a civil rights icon—all legitimate American saints. Each has their dolls.

You start to ask “Why—?”

The old comedian cuts you off. “They get the job done, son.”

“What the hell does that mean?”

He somehow manages to give you a side-eye, despite being almost entirely blind. You remember your dream that was not a dream, of LaSonia’s topsy-turvy doll tumbling out into the night, hellbent on destroying barriers. You imagine that scrum of plastic pickaninnies somehow derailing an SEC investigation. You recall the incompetent boob’s incomprehensible rise from real-estate shyster to Our President.

You wonder how the dolls can possibly do these things—do they scuttle around whispering in the ears of professors and stuffing ballot boxes? Or are they more like voodoo dolls, gathering in moonlit cabals to work their sympathetic magic?

And you wonder if the how of it really matters. Your dad was supposed to be in a morning meeting on the 102nd floor of the World Trade Center’s North Tower on 9/11. He missed it because he suddenly fell ill and crapped his pants in the town car on the way there. You and your family had called it “Luck”—but had it been luck? Or had it been Mr. Lips?

“You know what my mistake was?” the elderly comedian asks you.

“Drugging and raping 62 women?” you spit.

His face sours momentarily, and then smoothes. America’s Dad, firm but forgiving. The sonofabitch.

“My mistake was getting rid of my doll,” he says. “I believed my own lie: that I was better than the Devil. That civil rights hero I mentioned? He was ordained clergy, and even he didn’t get rid of his doll. He didn’t like it, and I know he never asked it to do a damn thing for him, but he kept it safe and sound—until it got burned up with the rest of his belongings when they firebombed his house. And you know how that turned out.”

You did. Everyone in America with a high-school education did: bleeding out on a grocery store parking lot just four days after the fire, assassinated by an idiot.

#

Late that night, LaSonia asleep, you creep home from a double shift at the prison. You and the Devil finally have your little talk.

“I don’t like you,” you tell the tupsy-turvey doll, “and you don’t like me. But we both love LaSonia.”

The doll sits on her shelf, White-lady end up, smirking. You take a breath.

“We both love LaSonia, and LaSonia hates …” You name the ex-rapper, the son of your dad’s old pal. LaSonia doesn’t give a shit about him—musically or politically—but any fool can see he’s riding the rails straight into being our next nightmarishly unqualified President.

Does the doll know you’re lying? Does she care?

You don’t know. Does a hammer care what it’s swinging at? Who holds it? Or does it smash and drive nails because smashing and driving is what it’s for, and being useful is its own deep fulfillment?

Mammy peaks out from under Mommy’s pale skirts. She winks.

You take a double dose of Valium that night. Your sleep is deep, dreamless, and overlong. You wake up late for work.

Rushing out of the house you glimpse Momma Mammy up on her shelf, holding illimitable dominion over all—but no longer alone: she has her white worm of an arm hooked around the wooden Shuffling Sambo’s crooked elbow.

Driving in, you hear on the radio that the FBI and ATF have raided Mr. Record Release Party’s ranch. Turns out he’s been a naughty, naughty boy.

You pull into the fenced and barb-wired prison parking lot, thrilled in a way you’ve never felt before.

It’s a dark thrill, more in the gut and pelvis than in your heart. Like a towering thunderhead, that dark thrill is heavy with possibilities.

Copyright © 2023 by David Erik Nelson All rights reserved

Cover art: Jane Iverson, Rag Doll, c. 1936, NGA 27514, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=82172132

novella, Expiration Date. (

novella, Expiration Date. (