Defense Distributed has been in the news off and on over the last half-year or so for their various “wiki weapons” 3D printed gun projects. The stated goal of founder Cody Wilson (a law student and hobby gun smith) is to obviate gun control legislation by making it possible for people to easily build guns from scratch in their homes using consumer-grade 3D printers. According to Wilson: “Anywhere there’s a computer and an Internet connection, there would be the promise of a gun.”

Up to now, DefDist was mostly known for their 3D-printed lower receiver (read “triggery bits” [UPDATE: I’ve *badly* mischaracterized the lower receiver here, and likewise botched the significance of a 3D-printed lower, in terms of gun control laws; I’ve added a footnote clearing that up.]) for the AR-15 (read “assault rifle”–this is the generic name for the popular, consumer-grade semi-auto version of the M16). The popularity of the AR-15 is based on the modulator of the platform–which, I know, makes it sound like a damn high-end camera, but that’s sort of the point of the AR-15: It appeals to a whole different demographic of shooters, distinct from “traditional” gun owners (who are largely hunters or target shooters). In other words, AR-15s are built to modify; if you want to “obviate legislated gun control,” then creating a durable, functional 3D-printed lower receiver for the AR-15 is a good first step, since it paves the way for “easy” full-auto conversion of the guns [UPDATE: this bit is also wrong; go look at that footnote!] (never mind that folks have been buying illegal conversion kits for ages; the point here is that it’s theoretically much harder to prevent the distribution of a few 3D printing files than it is to arrest some kook selling full-auto conversion kits out of his van in the gun-show parking lot).

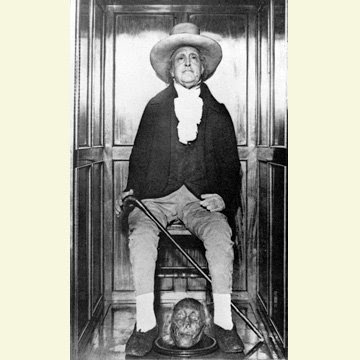

But DefDist made a much bigger splash in the news earlier this month when they released their first fully 3D printed pistol (shown on the left), the “Liberator” (the name–and to some degree the design–is riffing on this). According to Wilson, since he’s now got a functional design for an almost-entirely 3D printed gun (it also needs a metal roofing nail, to function as the firing pin), gun control is officially silly and over and totally pointless: “Any bullet is now a weapon.”

The news media and Capitol Hill promptly freaked the fuck out.

Should you?

Nope.

I’ve done a little 3D printing, lots of dangerous DIY, and more than a little shooting. What do I see here? Well, this is a single-shot .380 pistol (.380 is a popular caliber for self-defense: it’s small and low-recoil, but packs about twice the punch of a .22LR, which is not generally considered a “lethal round”). I’ve never touched one of these plastic guns, but the Liberator almost certainly has poor compression and accuracy (see how short that barrel is?). It takes *hours* to print (reportedly four hours for the barrel alone, which is *single use*–more on that below) using a pro-grade 3D printer that costs nearly $10,000. It’s likely that this gun, if printed on one of the slightly-more-common consumer grade, like a MakerBot Replicator (sticker price: $2,500) would explode on the first shot.

But, hey, the design is solid, right? I mean, you can download the “ready-to-print” files right now; it’s plug-n-play. Or so the say. Once you dig into the documentation that goes along with the print files, you find this little note at the end:

Before firing a barrel, we recommend heating acetone to boiling and treating the barrel for ~30 seconds to decrease the inner diameter friction, which increases barrel life from 1 round to ~10 rounds. Note that we recommend printing multiple barrels and using each only once. Swapping the barrels is simple and fast: rotate the barrel to release the locking cam. Pull up on the barrel. If the barrel cam broke, turn the Liberator upside down to remove the debris. Then drop your new barrel in and rotate it until it locks.

Yup; you need to boil the barrel in nail-polish remover to strengthen it, and even then they aren’t suggesting you chance it by firing more than once. There are also *lots* of specific instructions on how parts need to be oriented during printing in order to maximize the material strength (because of the way this style of printer lays up material, the resulting parts are stronger along one axis)–and all that just barely squeezes out a workable one-shot pistol.

Just in case you’ve never used a 3D printer, let’s be clear that these are nowhere near as “consumer-ready” as breathless media accounts make them sound. There’s *a lot* of fiddling around with obtuse software and hardware configuration even to print something rudimentary (like a whistle or bottle opener), and even then there are *lots* of easy-to-miss details that render a print useless. Right now, this technology is much more akin to a CNC router than a desktop printer. It is *not* “plug-n-play.”

The notion that this somehow qualifies as a weapon *anyone* could make is laughable in the extreme. I don’t know a ton of people, but each of them would qualify as *anyone*–they include engineers, makers of all stripes, shooters, and even a bullet proof glass manufacturer, for God’s sake–and *none* of them could make this gun.

So, just to recap, in order to print this gun you need a $10,000-ish 3D printer, lots of time, training in an idiosyncratic sub-set of computer-aided design, and if you wanna be legal, possibly a federal license. Meanwhile, to legally *buy* a gun you need $20 to $50, and likely will not be challenged with any sort of background check or ID verification. Will the price of those printers come down? Sure. Will the feedstock for those printers get stronger? Sure. Will the software to use them become better and more approachable as the skills become more common? Highly likely. Are there plenty of folks who don’t give a damn about getting that license to manufacture guns? You betcha!

But does the Liberator–or any of DefDist’s shenanigans–have any real impact on the viability of legislated gun control?

Not one bit.

Why? Well, first off, because our nation’s pawn shops and gun shows *still* have buckets upon buckets of cheap-ass MP-25s kicking around.

But even if that wasn’t the case, even if our Magical Wish Granting President[1] magicked away all the bad guns yesterday, Wilson’s Liberator *still* wouldn’t move the needle on gun control, or freedom from government tyranny, or home-defense, or anything. Why?

Because today, right now, any of you reading this can do a lil googling, make a quick run to the hardware store, and build a safer, better zip gun with less than $10 in parts, no specialized skills, and tools you almost certainly already have in your garage. (DEPRESSING PRO-TIP: White supremacists are especially adept at disseminating cheap, utilitarian zip-gun designs.)

The takeaway: Every bullet already *is* a weapon. That’s the point of bullets. Wilson’s 3D-printed Liberator isn’t a gun, and certainly isn’t “proof” of anything; it’s a prop in a piece of clumsy political street-theater, and the core goal of this performance art seems to be making a virtue of laziness: “See! Hard problems are super-hard! It’s OK not to try and solve hard problems.”

Lurking behind all of this, once again, is the conviction that a technological solution can sweep away a social conflict, pretending as though the core question (“How do we address America’s ~100,000 annual gun-dependent injuries and deaths?”) no longer needs to be addressed because one small portion of one suggested solution seems like maybe it’s no longer as salient.

Not to put too fine a point on it, but it likely comes as no shock when I point out that Cody Wilson is a young white-colored American male. I’ve noted over the years that young pinkish American men have the most acute difficulty in seeing how rarely technology magicks away our social problems.

There is some neat stuff going on with these DefDist “wiki weapons” projects–I like how the Liberator takes advantage of striation artifacts inherent in the printing process to make stronger components; I’d wondered about trying a nail-polish remover wash to mod 3D printed parts, and so I welcome Wilson’s stunning demonstration of efficacy–but the guns themselves aren’t one of the neat things. They’re sorta junky, and I’m having a lot of trouble in seeing how they bring *any* of us closer to a more perfect union, let alone anything approximating “Freedom.”

FURTHER READING: Farhad Manjoo has some interesting analysis here; I don’t know that I agree with the details (his thinking strikes me as narrative, which generally means it’s unlikely to predict what will actually happen), but I certainly agree with the broad strokes. If this is all piquing your interest, Forbes has *excellent* coverage on the development of the Plastic LIberator.

[UPDATE 05-14-2013] Almost immediately after I posted this Ben Brainerd–a friend with military small-arms training *and* extensive civilian gunsmithing experience–pointed out that the “AR lower [receiver] is not ‘triggery bits’. Those go *inside* the lower, and are currently pretty much impossible to 3D print.” He went on to explain that, for legal purposes, the lower receiver is the regulated portion of the gun, since it’s the key operable component. Thus, it’s the piece that bears the serial number. If you are buying a gun as components, the lower is the part that you need to get a background check before purchasing (provided you’re in a “background check” situation). Ergo, if you can produce a usable lower receiver *without* having to purchase one, you can effectively entirely sidestep in the background check issue, since all the other parts can be purchased without a check. (In an earlier Twitter conversation Ben had pointed out that none of this was really a game-changer anyway, since folks have long fabricated their own lower receivers, just to prove they could–for example, this AK-47 made from a shovel [FYI, beware of gleeful homophobia at that link]). So, while the 3D-printed lower receiver *does* make it easier for folks with no metal-working skill to circumvent some gun control efforts, it still requires expensive equipment and expertise, just in a different area (also, a little research indicated that even folks experienced with 3D printing and AR-type guns have had more than a little difficulty getting the kind of performance promised by DefDist for their 3D-printed plastic lower receiver).

So, *that’s* the point of the DefDist 3D-printed AR-15 lower receiver: Avoiding background checks. It doesn’t have any bearing on converting a semi-auto AR to full auto, because as Ben explained “anything in “fire control” (Trigger, hammer, bolt, etc) needs to be high-impact, so 3D is right out.” I suggest someone could fabricate these from steel at home using a CNC router–expensive gear, but I actually know folks who actually own them, so not that fanciful. Ben agreed: “CNC is how they’re made for real, for the most part, so yeah, that’d be the route for DIY conversion.” While large CNC routers are a specialized piece of gear few of us have in our homes, they are widely accessible (live in Ann Arbor, like me? Maker Works can hook you up–although they likely reserve the right to boot your ass out if you chose to make full-auto conversion kits in their facility), *lots* of folks know how to use them, and I’d be *shocked* to learn that the files for fabricating parts to do an auto-conversion on an AR-15 *aren’t* already floating around online. Oh, wait, 30 seconds of googling turned up an entire blog dedicated to using CNC machines to fabricate AR-15 parts–although not specifically for full-auto purposes. And a few more minutes turned up this page, which formerly hosted just such a file. So, yeah, it’s out there.

Continue reading “The “Liberator” 3D-Printed Plastic Pistol: A Thing You Don’t Have to Worry About #guns”