Burning Chrome was a favorite of mine in the mid-1990s, when I first read the title story in an Oxford sci-fi anthology I found for a couple bucks at a used bookstore.

Before that decade (and century, and millennium) was done, I’d read every one of these stories more than once, fascinated with the future Gibson painted, one I could see just around the corner. Some of these stories (like “Johnny Mnemonic” and “Burning Chrome” and “Dogfight”) I read over and over and over again. The best of these (esp. those last two) are really solid, tight, classic noir tales (albeit ones modeled after Jim Thompson’s The Grifters more than Dashiel Hammett’s gumshoes). The rest are, at best, stylistic sketching exercises; they more often have punchlines than plots. Gibson wrote all but three of these stories before Neuromancer, his debut and breakout novel (published in 1984.) Prior to 1982, Gibson doesn’t appear to have precisely known what a plot is. I’m not sure he’d argue with me on that; he’s said himself that although he’d been writing “stories” since the 1970s, the first one that was actually a proper story was ”Burning Chrome” (published in 1982, and basically a prototype for Neuromancer).

Cyberpunk is a future that looks an awful lot like the past, especially now (although even then, Gibson was firmly rooted in the past, sometimes formally—as with “The Gernsback Continuum”, other times more subtly, as with the noir plots he gravitates toward, and which become the heist/resistance themes that seem to form the skeleton of most cyberpunk stories still).

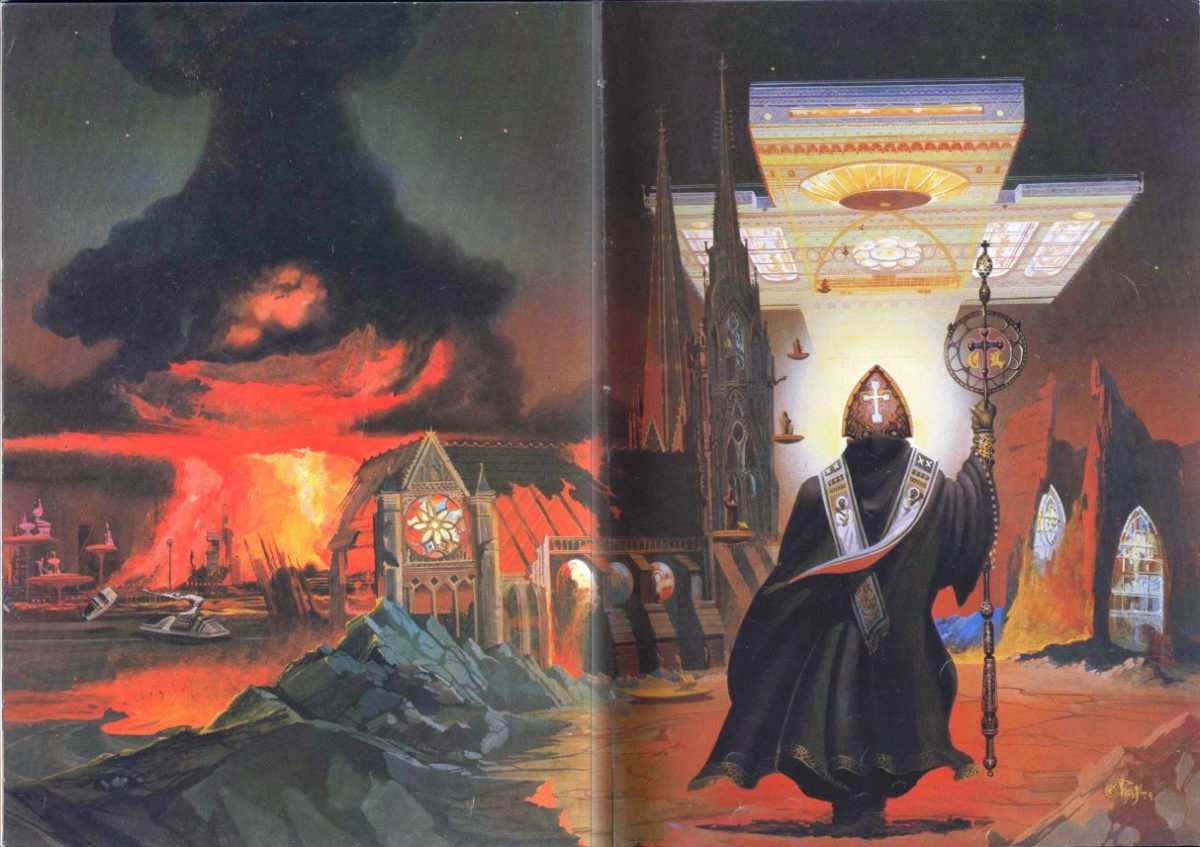

I’m old now, and Gibson, it turns out, is to me what Hugo Gernsback/1950’s “Populuxe“/Frank Frazetta/“Googie”/Eero Saarinen were to him. I think it’s appropriate that these are primarily visual artists and movements: Gibson has always been more of a visual artist and stylist than a writer, despite how culturally and politically prescient his writing has been. I’m given to wonder if that is why he’s proven so upsettingly accurate in his predictions (which I don’t think he thought of as predictions at all): the “Deep Pilot” might express itself in words, but runs its pattern matching on a purely aesthetic basis. We may be talking apes today, but at heart we will always be the monkeys that first daubed paintings of the world we hoped—or feared—we’d soon see on French cave walls.

“The future is already here — it’s just not very evenly distributed.”

William Gibson